The Geology of Post-Flood Mountain Uplift

The biblical account of Noah’s Flood, as described in the Book of Genesis, describes a cataclysmic event that reshaped not only the surface of the Earth but also its geological structure. According to a young Earth creationist perspective, the planet is approximately 6,000 years old, and the events of the Flood play a crucial role in understanding geologic phenomena. One of the significant aspects of this post-Flood world is the concept of mountain uplift, which can be seen as both a direct consequence of the Flood and a factor influencing subsequent geological formations. In this article, we will explore the geologic processes that would have led to the uplift of mountains following the Flood, using both scriptural insights and scientific interpretations that align with a young Earth viewpoint.

The geological framework around the event of the Flood presents a unique opportunity to delve into the evidence supporting rapid geological change. Many features we see today, including mountain ranges and valleys, can be understood through the lens of rapid processes and dramatic tectonic activity initiated by the Flood’s unprecedented stress on the Earth’s crust. As we examine the interactions of plate tectonics, hydraulic processes, sedimentation, and erosion, we will draw connections to the transformative effects of the Flood event while also affirming the scriptural narrative that undergirds this scientific inquiry.

The Biblical Context of the Flood and Geologic Change

The narrative of Noah’s Flood provides a backdrop for understanding the geological world’s transformation. The Bible indicates that the Flood was a global event, wherein the “fountains of the great deep” were broken up, and “the windows of heaven were opened” (Genesis 7:11). This suggests a level of geological upheaval that would not only inundate the Earth but also significantly impact tectonic activity. Within a young Earth framework, this account verifies a catastrophic model for understanding the earth’s geological history and structures. Consider the implications of such forces acting on the Earth’s crust—this event would have led to both sediment deposition in low-lying areas and significant uplift in other regions.

The Mechanisms of Uplift

Mountain uplift is primarily attributed to tectonic forces, generated by movements in the Earth’s lithosphere. In the context of the post-Flood world, several mechanisms combine to explain how uplift could occur rapidly and dramatically:

- Plate Tectonics: The theory of plate tectonics postulates that the Earth’s lithosphere is divided into multiple plates that float on the semi-fluid asthenosphere. The interaction of these plates—whether colliding (convergent boundaries), separating (divergent boundaries), or sliding past one another (transform boundaries)—can create significant geological features, including mountain ranges. Following the Flood, it is plausible that the stress exerted on the crust led to rapid faulting and uplifting of the Earth’s surface.

- Isostatic Rebound: As massive amounts of water shifted during the Flood, the weight over certain geological formations could have been relieved. Once the weight of the water decreased, areas of the crust previously deformed by the weight of the water began rising again, a process known as isostatic rebound. This significant adjustment in crustal balance would further amplify mountain formation and uplift following the Flood.

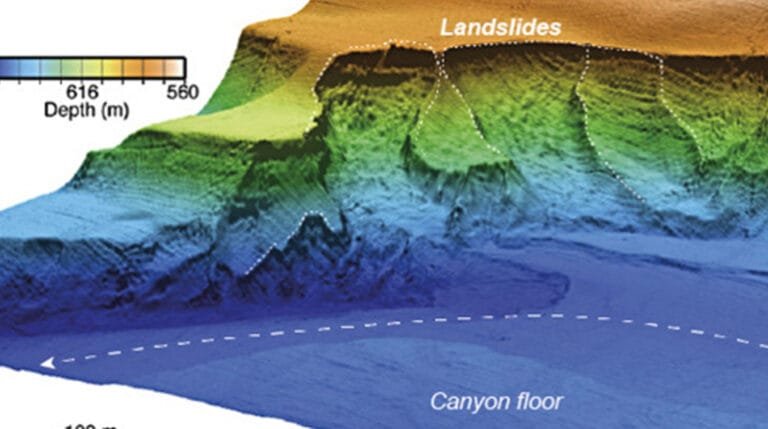

- Hydraulic Forces and Sediment Transport: The violent movement of water could have transported vast quantities of sediment across the landscape. Rapid movements and deposition could lead to geological forces that generate localized pressures, contributing to uplift due to accumulation and erosion. Sediment compaction also plays a role in shaping mountain ranges over time.

- Volcanic Activity: The aftermath of the Flood could also have encompassed significant volcanic activity, which is known to contribute to mountain building. The heat and pressure created during this event could have led to the formation of new land masses which, over time, would influence the mountain structures that we recognize today.

Post-Flood Uplift and Geological Features

The understanding of post-Flood uplift provides insight into various mountain ranges around the world. For instance, the Rockies, the Himalayas, and the Appalachians exhibit characteristics that align with rapid uplift theories. Below, we will briefly explore how these mountain ranges might relate to the post-Flood geological landscape:

The Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains are a testament to significant uplift processes. This range, stretching from Canada to New Mexico, is primarily composed of sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. The mechanisms of uplift could be traced back to tectonic plate interactions, where the North American Plate has experienced forces leading to the mountains we see today. In a young Earth context, the uplift of regions like the Rockies could have occurred shortly after the Flood, further affirming the narrative of a transformative global event.

The Himalayas

Similarly, the Himalayas, home to the tallest peaks in the world, are said to have formed from the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates. In a post-Flood framework, this mountain formation could align with increased tectonic activity as the Earth adjusted after the massive disruptions caused by the Flood. The rapid uplift would be consistent with the notion of a young Earth, where geological features formed at a much accelerated rate than traditional models suggest.

The Appalachians

The Appalachian Mountains present another compelling case. They formed earlier in the Earth’s geological history but experienced substantial restructuring due to post-Flood tectonic forces. The mountains emphasize the cyclical processes of erosion and uplift that followed catastrophic events on the planet—a hallmark of the post-Flood landscape.

Evidence Supporting Post-Flood Geology

While the Bible provides a framework for understanding the Flood, additional evidence can be sought from geology that concords with a young Earth perspective. Several key areas of study allow for a better understanding of the implications of mountain uplift in a post-Flood world:

- Fossil Records: Fossils found at significant elevations offer evidence of rapid sedimentation from the Flood’s aftermath. Many sea creature fossils can be found in mountain ranges, suggesting the ocean’s reach was far more extensive before being altered by the Flood.

- Stratification: The stratified layers of rock found in mountain ranges can be interpreted as evidence of rapid deposition and subsequent compaction following the Flood. The sedimentary structures provide insight into the environmental conditions during and after the catastrophic event.

- Gaps in Geological Time: The concept of geologic time presents challenges for a young Earth perspective. Notably, the absence of transitional layers in certain formations suggests rapid formation processes that can be explained through a post-Flood model rather than traditional slow and gradual sedimentation.

Conclusion

The geology of post-Flood mountain uplift provides a fascinating intersection between biblical history and scientific inquiry. When viewed through a young Earth lens, the account of Noah’s Flood offers a compelling premise for understanding the processes that created and shaped the mountains we see today. The processes of uplift driven by tectonic activity, hydraulic forces, sedimentation, and volcanic action reflect a world forever altered by a divine act of judgment and grace. Through an examination of both scriptural evidence and scientific interpretations, believers can gain a deeper appreciation of God’s handiwork in creation and the ongoing wonders of the natural world. This comprehensive understanding reflects the harmony that can exist between faith and science, allowing for thoughtful engagement with both the Bible and the dynamic history of our planet.